Remember the ‘RICE’ protocol? Rest, Ice, Elevate, Compress? Well, the guy who invented it doesn’t agree with it.

“My RICE guidelines have been used for decades, but new research shows rest and ice actually delay healing and recovery,” says Mirkin, now 84.

“If your muscles are sore, you can relieve that pain with ice. But the inflammation causing that soreness is actually bringing healing to the body; by icing, you “dampen that immune response,” he says. “You think you’re recovering faster, but science has shown you’re not.”

When Mirkin wrote his book, he was simply reporting the anecdotal evidence of doctors who saw a temporary decrease in swelling and pain from immobilization, ice and compression.

“In 1978, inflammation wasn’t even in researched literature, but everyone was resting, putting people in casts, wrapping things tightly with ice,” Mirkin says.

“I didn’t recommend anything on the basis of extended research. I recommended what everyone was doing at the time.”

“And because “RIC” just wasn’t that catchy, and a gravitational assist can help blood and fluid be reabsorbed by the body, Mirkin added an “E” at the end for “elevation.” It made for a nice slogan: “RICE is Nice.”

Yet it is still taught in medical and physical therapy schools today and is listed on the National Institute of Health website as the top treatment for acute and chronic sports injuries.

How Icing Adversely Affects Injury Repair & Healing

The first question is why are we icing?

Our goal with injury is to prevent further loss and facilitate the repair and healing of tissue that’s been damaged.

Question: how does ice help that process? It most likely doesn’t and may even make it worse. Here’s why.

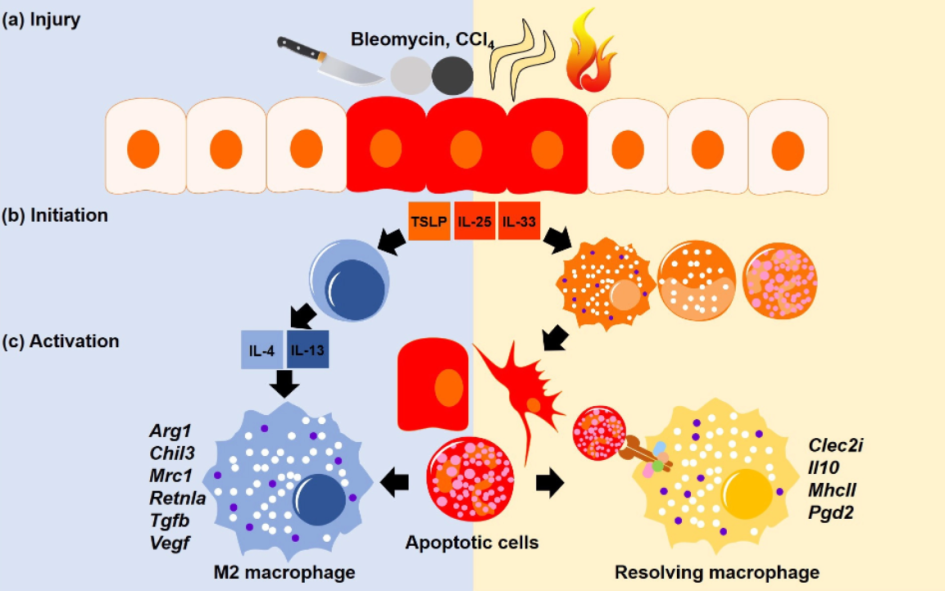

When tissue is damaged, the immune system initiates that inflammatory response, which a 2010 study published in the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology Journal showed is necessary to heal damaged tissue and repair muscle.

The body deploys its repair and cleanup crew in the form of macrophages, white blood cells that engulf and digest cellular debris. They produce the protein insulin-like growth factor 1, which is required for muscle repair and regeneration. The same study showed that blocking inflammation delays healing by preventing the release of IGF-1.

This figure doesn’t represent perfectly what is happening during a musculoskeletal injury but is an example of a typical wound healing response you might see in response to an ACL surgery for example.

The theory about why icing may be detrimental to managing injuries is because ice delays the above healing process by constricting blood vessels and allowing less fluid to reach the injured area, as demonstrated in a 2013 study in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research.

This research showed that topical cooling delays recovery from eccentric exercise-induced muscle damage. Additionally, a 2015 article published in Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy showed that the narrowing of blood vessels caused by icing persists after cooling ends and the resulting restriction of blood flow can damage otherwise healthy tissue; implying icing may cause more damage on top of the existing injury.

As far back as 1986, a study published in the Journal of Sports Medicine showed that when ice is applied for a prolonged period, lymphatic vessels become more permeable, causing a backflow of fluid into the interstitial space. That means local swelling at an injury site may increase, not decrease, with the use of ice.

Fluid & Swelling

Inflammation and swelling have been deemed the enemy, but maybe they’re not.

Inflammation is a process the body uses to heal tissue, while swelling is a byproduct of that process,” says Dr Joshua Appel, an Air Force flight surgeon for the 306th Pararescue Squadron and Chief of Emergency medicine at Southern Arizona VA Healthcare System.

“When you recruit inflammatory markers to an acutely injured area, with that comes fluid. The body knows how to heal itself, so you’re not getting too much fluid. But you can have not enough evacuation.”

Swelling maybe not be a good or bad thing. Swelling may be merely an accumulation of waste at the end of the inflammatory cycle you have not yet evacuated. So how are you going to evacuate it? Activate the muscles in and around the damaged site, restore circulation and the lymphatic system will move the waste through.

The theory is, icing traps the waste in and around the damaged site and prevents the natural flow of oxygen supply to the tissue. This could cause additional damage and swelling (by causing a backflow from the lymphatic vessels into the interstitial space AKA a congestion of fluid).

While that’s happening the icing has dulled your ability to sense pain. So now you can enter potentially harmful ranges of movement your body would ordinarily tell you are painful. How could that possibly be a good plan to rehabilitation?

Summary

Is the body’s healing response of swelling and inflammation a mistake and should be blunted? At this point, probably not.

Why do we ice? Because we have pain that may be coming from swelling. Icing will numb the area but how is this helping the repair response?

Is your goal to take away the pain or take away THE REASON AND CAUSE its pain?

“Analogous to are you using drugs and alcohol to numb pain or getting to the root of why you want to numb the pain in the first place?”— Gary Reinl

Grains Of Truth

There are exceptions to every rule. Icing has a very useful role in reducing pain and exerting a temporary analgesic (pain reduction) effect. This should not be understated because we can use this tactfully to our advantage.

If someone is in a lot of pain that is severely affecting daily function and quality of life then icing and medication could easily be justified.

If an athlete is in the middle of a finals game and has had a patellofemoral or tendinopathy flare-up. Then icing a player and getting them temporarily out of pain and feeling better could be the difference between winning and losing.

We shouldn’t be so dogmatic in either direction to not see the grains of truth behind an argument. I hope that’s added some clarity on the efficacy of icing.

Better Alternatives To Ice / Cold Exposure:

Lymphatic System

While we need to protect the tissue from being over-stressed we use movement to facilitate repair.

How does the body clear swelling?

Most of the particles are too large to move through the vessels of the circulatory system, so they must instead be evacuated through the vessels of the lymphatic system. The lymphatics, though, are a mostly passive system, reliant on muscle activation; movement/muscle activation is necessary to propel fluid through the vessels. Sitting still with an ice pack creates the exact opposite effect.

Muscle Stimulation

If an injury is too painful or the area is too fragile for any type of voluntary movement, consider using a neuromuscular electrical stimulation device

Such devices create non-fatiguing muscle contractions, allowing waste and congestion to be removed by your lymphatic system, which is driven by muscle contraction. It’s movement without painful motion.

Activating muscles in and around the damaged site facilitates angiogenesis (formation of new blood vessels) which helps to recapilirise and re-build that network of vessels around the damaged site. It will also help mitgate muscular tissue atrophy which is common in healing injuries.

METH, PEACE & LOVE

In 2011, Canadian exercise physiologist John Paul Catanzaro coined the term METH — Movement, Elevation, Traction, Heat — as an alternative to RICE.

In April 2019, two British physical therapists proposed another acronym in the British Journal of Sports Medicine: PEACE — Protect, Elevate, Avoid anti-inflammatory modalities Compress, Educate

LOVE — Load, Optimism, Vascularization, Exercise.

All these ideas bias prioritising movement over decreasing inflammation.

For more education on maximising health, wellness and performance follow me on Instagram, Facebook & YouTube or see my coaching services here.